|

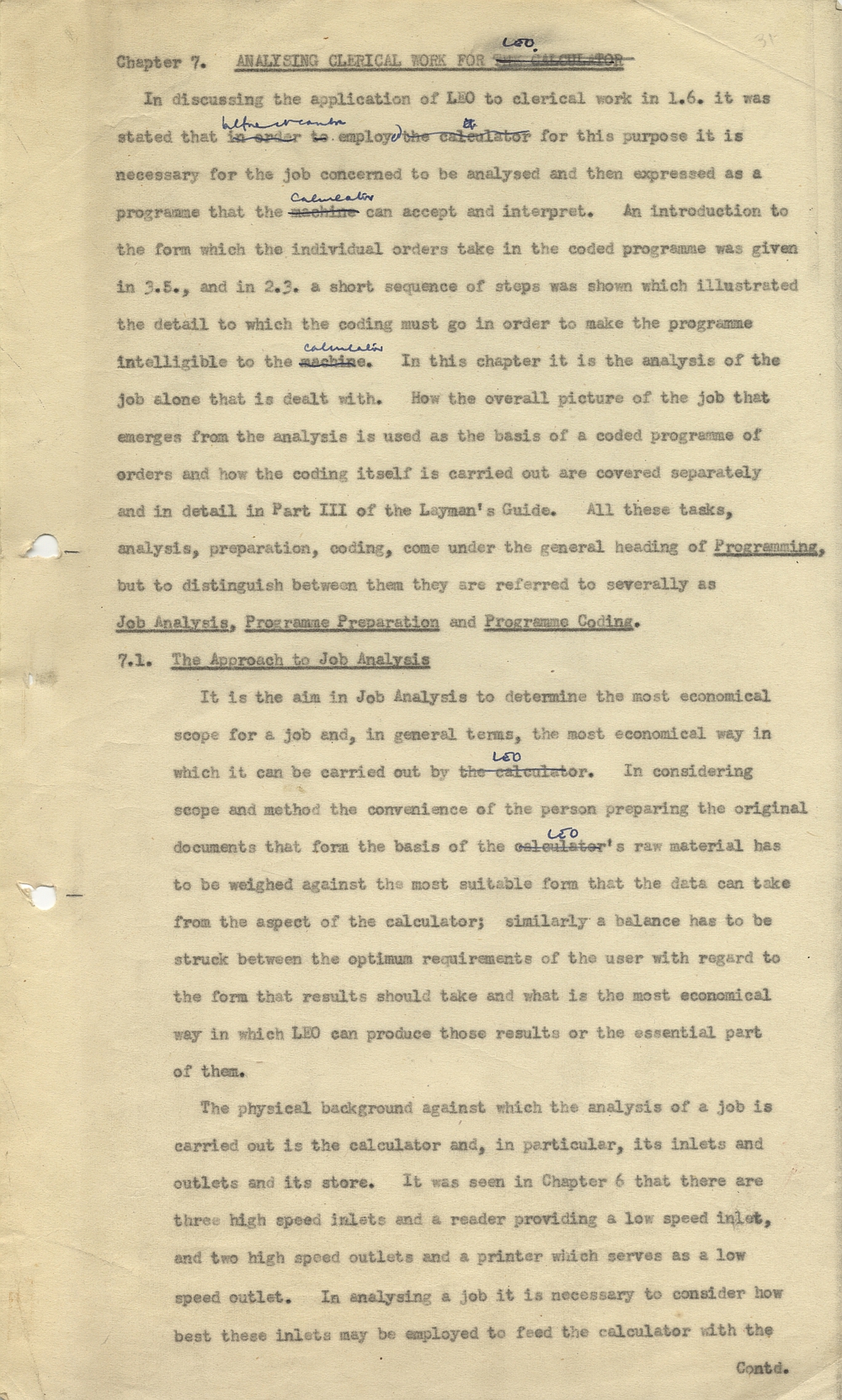

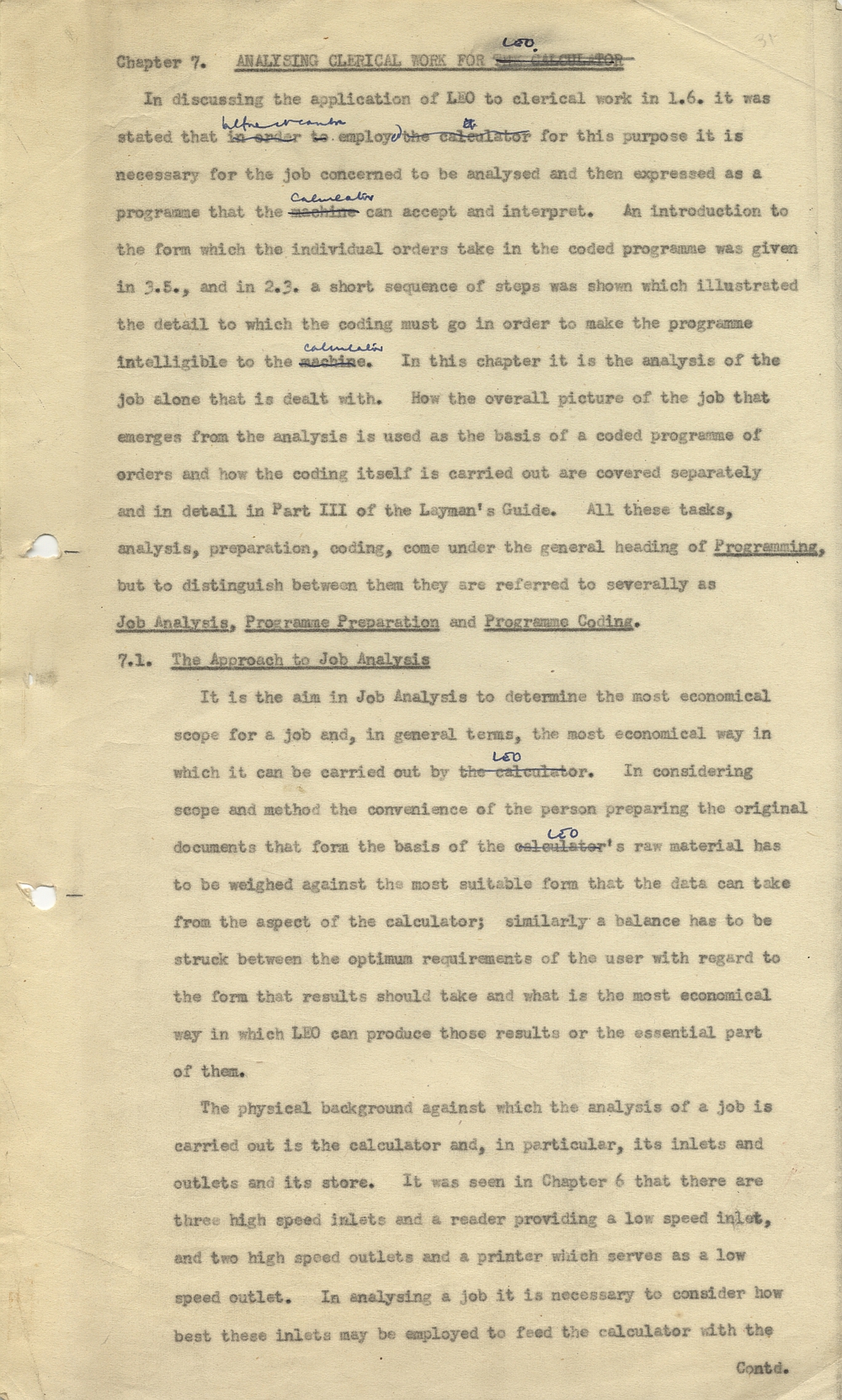

Headed 'Chapter 7.', the draft text is from 'The Layman's Guide to LEO', though there is no indication in the document.

The title was originally typed as 'Analysing Clerical Work for The Calculator', then corrected in pencil.

Includes flowcharts, tables and diagrams. Annotations in pen and pencil in David Caminer's hand.

Related materials:

Research comments: This seems to be a chapter of the Layman's Guide to LEO.

It is interesting that the document refers to 'inlets and outlets' rather than 'input and output'. The author states that the intention when translating a job to the machine is always to minimise the time for which it is idle and awaiting data, the reality being that the 'calculator' itself can work at much faster speeds than either the input or the output. Different 'inlets' can provide different data to the machine and the machine can create new data that are then used for other jobs, by being stored on magnetic tape.

The document lists the kinds of tasks LEO can do from basic counting type functions (at a rate of 250 counts per second at least), to adding, subtracting, multiplication, and division including in sterling, decimal and vulgar fractions, and percentages (adding/subtracting at 250 times per second; multiplication at 80 per second). It explains that division is generally to be avoided because the calculator can only divide by making use of the other arithmetical processes. LEO can round off figures to the nearest pound in sterling or weight.

The document then suggests the kinds of repetitive clerical work that the computer could do, including invoicing, wages and stock valuations, detailing an example of how LEO would calculate invoices and do 'end of day' summaries automatically by being able to recognise 'signposts' given to it by its programme of orders. This hints at the key difference between LEO and other very early computers; LEO has been designed to perform "comparatively simple calculations repeated many times" (point 7.2.3.2. in the document), the very definition of clerical work, unlike other calculators such as the Manchester Mark I and EDSAC that needed to perform very complex calculations but do them only a small number of times.

How to code data so that the calculator can identify things like the sex of an employee or what part of a restaurant they work in (section 7.2.8. in the document) is also explained. We do this easily using spreadsheets today, but in the 1950s coding data in this way was a relatively new idea. Similarly, LEO can balance totals and provide balanced control accounts (management information) too (section 7.2.9), much as we would today with spreadsheets and accounts software.

Section 7.4 starts with a summary of why a LEO is good to have: "...despite the high cost of building LEO, the speed of operation and the possibility of doing the whole clerical job from the taking in of the original data to the preparation of the final results make its practical value very great.". This section roots the machine within the wider processes of a business by answering the question 'where is the scope of a LEO job to begin and end?" and points out that how processes are divided up might not follow the usual human departments of a business. In fact the document warns against "pre-judgements arising from the conventional grouping of tasks" (pp49). The document then breaks down the process of working out what data/records a job for LEO might need as input and output, and then suggests thinking through what other business tasks make use of the same or similar data. Only in this way will the practicality of using a computer become clear to someone considering buying one.

Section 7.6.2. looks in detail at how to plan the job of invoicing 10,000 customers each day out of a total pool of 50,000 customers, whose orders are taken by 400 'travellers' (salespeople) who then post the orders to head office for processing on LEO. Customers usually order around 20 items each time but can order between 1 and 80 items and the prices for the items are stable, although discounts can be applied. Each customer has a credit limit that must not be breached. The 'travellers' need to be banded together for analysis. A chart (pp 84/5) offers an overview of the types of data required, and how the timing of the data intake via the various 'inlets' needs to be managed so LEO can function.

Section 7.7 focuses more on the 'outlets', a teleprinter using pre-printed continuous paper (max 7" wide with a maximum of 6 carbon copies) and a series of 'recorders' (magnetic tapes in 'tape-boxes'), the data on which can be fed back into the machine. (LM)

Date : undated, mid-1950s

Creator : David Caminer

Physical Description : 1 file (116 pages), paper; typescript with annotations

Provenance :

From David Caminer's papers.

Archive References : CMLEO/DC/LP/54767

, DTC/6/1

, DCMLEO20190822001-010,DCMLEO20200810001-076,DCMLEO20200817500-530

This exhibit has a reference ID of CH54767. Please quote this reference ID in any communication with the Centre for Computing History.

|

|

This document has been scanned and is available to view online.

Copyright

Lyons copyright

File Size: 9.59 MB

|